By Hillary Anger Elfenbein; Washington University in St. Louis

So your three-year-old comes home and tells you that he wants chocolate for dinner. Now what?

If you’re anything like me, you start by trying to sell him on what else you’ve prepared. This approach doesn’t work very well, and then he throws himself on the floor.

When this happened recently, I took a deep breath and reached for inspiration from one of the best advice books out there: “Playful Parenting” by Lawrence Cohen. The fundamental point is that you can often get better behavior from humor vs. so-called discipline. With this inspiration, I turned to my three-year-old and showered him with praise for telling such a side-splitter: Harry wants chocolate for dinner! Everybody, come over here so Harry can tell you his joke himself. Harry KNOWS that we eat chocolate only for dessert, but he’s pretending he wants it for dinner! Everyone, Harry is so clever to tell such a funny joke. Meanwhile, my husband, older son, and I are smiling and clapping for him, and pretty soon the little guy is walking over to the dinner table for spaghetti.

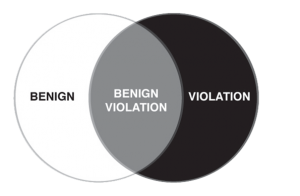

You know, everyone likes it when some social scientist comes along and shows them why it’s a good idea to do what they were already doing, while giving them a novel justification they didn’t already have handy to tell the in-laws. This is one of the many appealing features of Peter McGraw’s benign violation theory of humor. The benign violation theory is elegant and has predictive power from business marketing to managing three-year-olds. As a guest blogger for Pete, I shouldn’t go ahead and describe his whole theory—but, just in case you ended up on his page while trying to buy shoes—let me briefly summarize. McGraw argues that humor is at the intersection of what is benign and what violates norms. If a three-year-old asks for noodles, that is not funny because it’s not a violation. If a three-year-old tries to hit his ten-year-old brother with a baseball bat, that is not funny because it isn’t benign.

By using humor to recover, we can prevent a showdown. Life is sometimes overwhelming for three-year-olds. By releasing the tension that they did something

The benign violation theory can help us predict what kids find funny: it’s what is just at their learning level. It’s not funny if they definitely get it, or definitely can’t get it. They find funny what’s in the middle, where there is a struggle to define what’s right yet they are in the process of figuring it out. Peekaboo doesn’t work until babies start on object permanence, and it doesn’t work for teenagers. Children laugh at things to show off to you, by giving you the meta-knowledge to know they know these are violations. We try putting clothes or shoes on the wrong person, or putting things on our head that don’t belong on our head. Incidentally, if you have boys in the house, farting is always funny. I once asked a friend with a boy going off to college when her son stopped finding farting jokes funny, and she said she would let me know.

With children, it’s important to distinguish laughing-at vs. laughing-with. In McGraw’s terminology, laughing-with suggests that the violation is benign to the kid too. Laughing at suggests that the violation is benign to the laugher, because the laughee is too powerless to be harmful. Kids are very sensitive to this, and you need to make sure they really know they are part of the telling.

I’d like to pretend this approach works every time, and that my house is a picture of perfect harmony, but that would be a lie — and my husband will probably read this blog and call me out. To me, the best part is letting the parents laugh too, and release the tension of having a three-year-old. Toddlerhood is the best of times and the worst of times. Letting kids have an outlet to accept their various constraints helps us to keep things at least more sane. In raising children, you can see just how many norms you instill are merely a social construction—and every now and then, you might just decide to go with the benign violation, rather than laugh at it. Because, seriously, it’s pretty ridiculous that you can never have chocolate for dinner.