This post was originally published on Huffington Post and was co-authored with Joel Warner.

The studies run in the Humor Research Lab often require subjects to create something funny, like a write a joke or come up with an amusing caption. But when other folks are asked to rate what they’ve come up with, we run smack into an unfortunate truth: Most things are just not that funny.

Take a recent marketing study I ran with Caleb Warren. In it, research assistants asked undergraduates to create funny advertising headlines for a made-up company, “Thriftonline.” There even was a funny-looking image of a couple to facilitate the process.

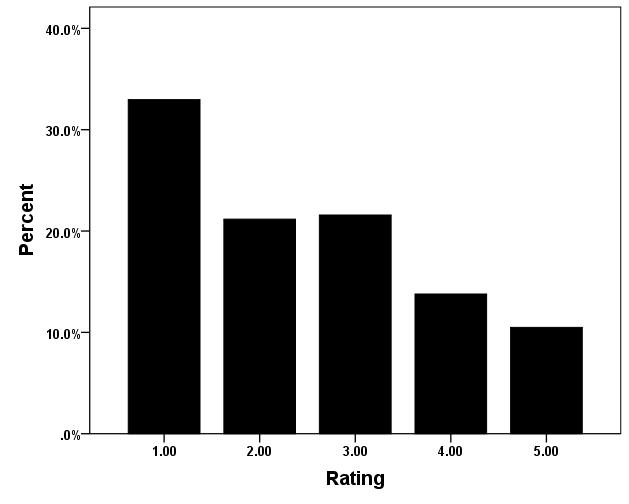

Then another group of undergrads judged the headlines on a five-point humor scale from “not funny” to “very funny.” Only 10 percent were judged to be very funny. Among the top scorers? “Because looking this bad never had to be expensive.” The vast majority, however, were mediocre. The average rating fell below the scale’s halfway point, and the distribution is skewed toward the non-funny side of the scale. In other words results skewed towards stinkers such as, “Come get your nerd.”

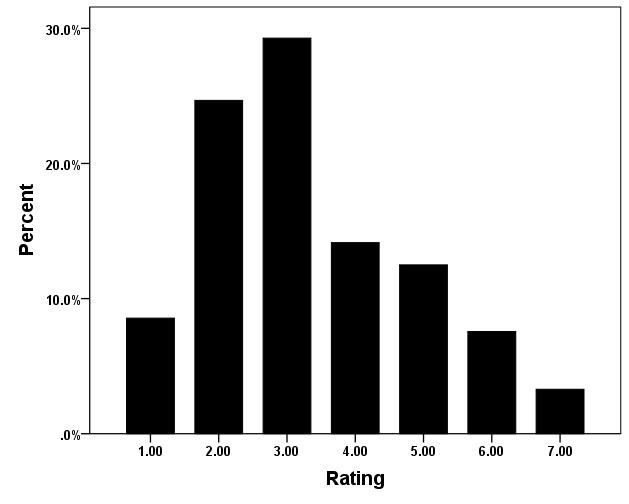

These results aren’t unique. Caleb and Jonah Berger, a Wharton professor, recently ran a study in which research assistants rated YouTube comedy clips on a seven-point rating scale from “not funny” to “very funny.” The results were similar.

Unfortunately, people also don’t spend very much time finding things funny. In a 1999 study, Rod Martin and Nicholas Kupier asked adults to keep a laughter diary. The researchers found that the average person reported only 18 episodes of laughter per day.

Why aren’t things funnier?

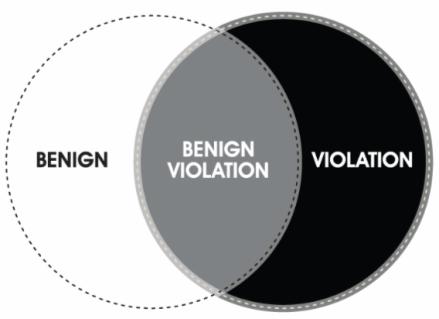

To understand the “not funny” effect, it helps to understand what makes things funny begin with. Building on work by Tom Veatch, Caleb an I have proposed the benign violation theory, which suggests that humor arises from perceiving something to be wrong, unsettling, or threatening (i.e., a violation) while also realizing that it is in some way okay, acceptable, or safe (i.e., benign). Tickling (at least when it is done by someone you trust) is a benign violation – a physical attack that does no harm.

The idea of a benign violation suggests that there is a sweet spot to comedy, that humorists fuse together just the right amount of pleasure and pain. In that way, a humor attempt has only one shot at succeeding, but two shots at failing. To fail, it can be too benign, and hence boring, or it can be too much of a violation, and offend in some way. What makes the task even tougher is that timing matters – the benign and violation appraisals need to occur in close proximity to each other. In short, it’s far easier being not funny than funny.

Making things funnier

Does that mean everyone should throw in the comedic towel? Not at all, since the world would be a far less interesting and entertaining place if folks stopped telling jokes, stinkers included.

Instead, take a few strategies to heart as you try to tickle your next funny bone:

1. Try a lot. Since most things aren’t funny, the best solution is to simply try to be funny more often. A theme from my Humor Code travels is that the world’s funniest people generate many, many ideas during the humor creation process – whether they are writing headlines for the Onion, drawing cartoons for the New Yorker, or dreaming up ads for the Super Bowl. Take a close look at how stand-up comedians do their job, and you’ll find that they spend their days writing many jokes and their nights testing them. As a result, the process of creating a solid hour of stand-up can take up to a year (as an example, watch the movie Comedian, which details how a stand-up legend like Jerry Seinfeld even struggles to create new material.

For the non-professional, just make a concerted effort to inject humor into casual interactions – with the barista at the coffee shop or the customer service agent at the airport. Sure, most of these attempts won’t kill, but eventual a few of them will truly shine.

2. Start with the bad. Mark Twain wrote, “The secret source of humor is not joy but sorrow; there is no humor in Heaven.” Because there is nothing wrong in heaven (i.e., no violations), there is nothing to laugh about. Jerry Seinfeld’s approach to comedy illustrates this principle. By humorously highlighting the things that are wrong with everyday life, he conjures humor out of everyday situations

For everyday folks, the “Seinfeld strategy” can be as simple as noticing that the things that seem awry are actually the best material for a joke, quip or witticism.

3. Be playful. Life can be stressful. Yet, a consistent theme in humor literature is that humor is often associated with safe, playful (i.e., benign) situations. Sarah Silverman’s approach to comedy exemplifies this. The popular female comedians takes extreme violations about age race, creed, or color and makes them benign by, say, weaving them into a cutesy song.

The “Silverman strategy” can be tricky to implement. The last thing you want to do is offend a friend or colleague by stepping too far over the line. So first, make sure everyone is in the right mood. At work or at home, try to create a culture that encourages a playful and fun (yet also respectful) atmosphere.

Move the needle

These strategies might not turn you into the next Chris Rock or even the life of the party. But considering how humor has been shown to improve people’s happiness and helps build social relationships, making life funnier, even just a little bit, is surely worthwhile. Sure, most things aren’t funny. But if you can a few more things humorous, you’ll reap the benefits.